My Parents

The story always begins with my parents, Carlos y Maricruz. They immigrated from Guatemala in the 1970s and were looking for opportunity, both for themselves and for the children they hoped to have one day. And indeed, by 1990 they had five children, two boys and three girls, of whom I am the oldest. My parents placed a high value on education because they themselves desired it, but were limited by their circumstances. My dad is the eldest of ten siblings and had many responsibilities as a young man and only studied up to the eighth grade. My mom on the other hand worked since she was five years old and had to stop her education at the sixth grade.

At eight years old, my dad helped my grandfather by planting and harvesting beans and corn in the family plot. The harvest was meant to supplement the family’s main source of income—my grandfather’s tailor shop. My dad also started helping out in the shop at age twelve, was sent to the city to apprentice at thirteen, and by fourteen years old he was serving customers by himself. At nineteen years of age, my dad opened up his own shop and was trying to complete his education at the same time. Yet it was difficult to do so, thus two years later, in early 1973, my dad made the journey to the U.S. to set the foundation for our family’s future, even though he was not yet married to my mom.

My mom, on the other hand, is one of seven and only two of her siblings had the opportunity to study beyond the sixth grade. Unfortunately, my mom was not one of them despite being good with numbers at a young age. By the age of seven, my mom would take a ten-mile bus ride to buy cheese at a cheese factory and then take another thirty-mile trip to the city to sell the cheese at the market. She also needed to make it back home by noon to eat lunch and attend school from 1–6 pm. Thus, at the age of seven, my mom knew how to mentally calculate change, manage credit, and navigate a complex system of transportation! By fourteen, my mom was working full-time at a textile shop in downtown Guatemala City, where she eventually met my dad. By 1974, my mom was ready to pursue bigger opportunities to continue helping her parents while joining my dad to get married and start a family of her own. To this day it is difficult for me to fathom that she traveled through two countries by herself at seventeen! My mom is tenacious and a main reason for our success.

My parents ended up living near downtown Los Angeles. Fortunately, my dad’s skills as a tailor and my mom’s experience at the textile shop allowed them to quickly find full-time jobs in the textile industry of L.A. As they navigated the culture of Los Angeles, they also spent a lot of time worrying about la migra [1] and had a few anxious moments. But by 1975, my parents were able to become permanent residents because they had a child born in the U.S.—me. In turn, my parents became the gateway for the rest of their family to also enjoy the freedoms and opportunities that the U.S. offered. There are now many college graduates and business owners among my cousins and their children because of the risks my parents took to gain a better life for the entire family.

Compared to my parents, my siblings and I have lived a life of privilege. Not only did we have the basics in life, but we were able to pursue extracurricular interests and not worry about having to support our family as our parents supported theirs. Yet it was not easy for us to navigate our journey in the U.S. We still had the challenge of pursuing an education in a school system that underserved and continues to underserve our communities.

Early Life

Although I remember that I liked going to school, I also remember that my parents couldn’t always help me with my homework. This probably came from my earliest memory of struggle—I didn’t understand what a certain first-grade assignment was asking me to do and my parents didn’t know enough English at this point to help me. I remember feeling devastated that my parents couldn’t help me and that I was not going to be able to complete my homework. I must also admit that the only parts of math that excited me in school were the timed exams on basic computational skills. This probably came from the fact that my parents enjoyed playing number games with us and encouraged us to be quick with mental math. In fact, the only two school math-related memories that I have are the following: On the first day of school, my fifth-grade teacher, Ms. Tanner, told us that she loved math and my sixth-grade teacher told us that if we divide by zero, the answer is zero. My sixth-grade teacher’s mistake was caused by a question of mine. I remember that she took out a calculator, punched a few numbers, and told us the answer was zero. As you can imagine, this affected me greatly when I took calculus in high school and I didn’t figure out what she did until I played with the district’s basic calculators as a teacher fifteen years later. When you try to divide by zero, the calculator screen does show a zero, but it also shows a capital E in small print next to the zero to indicate that it is an error.

At home, mathematics was more exciting and deeper than what I learned at school. For example, as soon as I learned how to count, before I turned five, I started counting every car I saw on the freeway when we visited Tijuana, Mexico. When my mom asked me why I was counting the cars, I told her it was because I wanted to get to the last number in the universe. This pursuit of finding the “last number” continued once I was in elementary school. About the time I was in fourth grade, our parents bought us a book that contained math puzzles and stories. One particular story intrigued me. It was about a girl who was hired to rake her neighbor’s leaves, and the neighbor offered to pay her in one of two ways. She could either receive $100 a day every day for a month or she could start with a penny today, two pennies tomorrow, four pennies the next day, and so forth doubling every single day for a month. The book then asked the reader to determine the best choice for the girl. I remember not looking at the answer because I wanted to explore this problem myself and I was surprised to discover that getting paid a penny on the first day and then doubling every day would be the best option. This “doubling” story also reminded me of the problem that I really wanted to solve which was to discover the “last number” of the universe. I decided on a new “strategy”—I would start at 1 and double each number until I found the “last number” I kept filling out paper after paper with numbers and my mom just let me compute because it was keeping me out of trouble. Finally, she asked what I was doing, and I told her that I wanted to get to the last number of the universe and that I had “discovered” a new technique that would allow me to get there faster. My mom looked at me quizzically and left me alone again as I filled out more sheets of paper with ever increasing numbers. Finally, she felt bad for me because she told me that there was no such number. I was shocked and I remember doubting her quite emphatically. She then challenged me to think of the largest number that I could and I said a googol times itself a googol times—I had recently learned from this book that a googol was a one with 100 zeros behind it, 10100. She told me that she could think of a number bigger than mine and I was dumbfounded! How could this be? She replied by stating that she could add one to the number I gave her, and my mind was blown! In fact, she insisted, she could always add one to any number I could think of and so this meant that there could be no “largest number.” I fell in love with my mom’s argument—my first proof by contradiction—and I should have known then that I was going to pursue math as a field of study.

Nonetheless, my family was not aware that we could pursue math as a field of study, and they did not possess the means or knowledge to encourage or provide me with the opportunities that could have helped deepen my passion for mathematics. Even a few more math books could have made a difference, but my parents trusted that school would provide for all of my educational needs, including the mentorship that I needed. Unfortunately, there was nothing at school that intrigued me as much as this book or my mom’s knowledge of mathematics, and this was part of the reason that later in life I wanted to teach in my community. I wanted our students to have their curiosity encouraged the way my mom encouraged mine.

Regardless, by sixth grade, I motivated myself by trying to show the world that Latinos could perform as well as anyone at school. It was going to be a proof by existence, not knowing that mathematicians like Bill Velez and Rodrigo Bañuelos were already opening doors for me. My dad kept encouraging me to show the world that Latinos were more than how they were portrayed in the media. Thus, my mission became to excel at everything, from math to English to baseball. I was going to outwork everyone and earn the best grades, even though there was nothing in my previous academic record to suggest that I could. But by the end of sixth grade, I had earned straight As, except for handwriting. I was so upset that I focused on handwriting all summer long so that I could earn straight As in seventh grade, not knowing that handwriting wasn’t graded in junior high. But it didn’t matter—in fact, it strengthened my resolve to be the best.

Math kept capturing my attention. For example, in eighth grade, I remember walking home one day with my friends, not listening to their conversation because I was so intrigued with the idea of the commutative property of multiplication and how it was so succinctly encapsulated in the symbols ab=ba. I remember mentally multiplying different numbers to confirm this statement and how awed I was by the power of symbols. I also loved to prove theorems in geometry—they felt like puzzles, and it reminded me of my book. However, what I needed most and wasn’t receiving was guidance in developing my curiosity in mathematics.

But not all was lost—I was lucky to have two adults at Sierra Vista High School (SVHS) who really cared for my well-being and who provided the mentorship I needed to fulfill my dream of obtaining a higher education. One was my English teacher, Ms. Kelly, who intimidated us, but who really wanted the best for us. The other person at SVHS who took care of me was our career counselor, Ms. Dunn. Both Ms. Kelly and Ms. Dunn believed in me more than I believed in myself. In fact, Ms. Kelly and Ms. Dunn would team up on me so that I would fill out scholarship applications. In one particular instance, Ms. Dunn took me out of Ms. Kelly’s class because I had not turned in a scholarship application that required letters of recommendation from community leaders. I disqualified myself because I personally didn’t know any community leaders. Ms. Dunn was exasperated with me and called my mom to ask her if she could secure the letters I needed. Ms. Dunn then sat me down so I could finish the application. By 3 pm mom had secured the necessary letters and was at school to pick me up. Ms. Dunn ensured I finished my application and sent us on our way to the post office to turn in the application by the deadline, 5 pm. It turns out that because of my involvement in our choir at Saint John the Baptist Catholic Church and my parents’ involvement in a family ministry, my mom was able to secure a letter from our pastor and from a city councilman. Thanks to Ms. Kelly, Ms. Dunn, and my mom this scholarship and many others guaranteed that I had less than $10,000 in debt after I graduated from UCLA.

Looking back, I wish I would have had this type of mentorship in math and science. Although I took all of the advanced science and mathematics courses that our school offered, no one really tried to encourage me to pursue either as a career. I wonder if we, sons and daughters of immigrants, weren’t expected to pursue these types of careers. We were definitely not exposed to anyone who “looked like us” who pursued mathematics in college. Thus, even though I never owned a computer and did not know what computer science meant, I still chose computer science as my major when I applied to universities. In 1993, there was no way that I was seriously contemplating a math major.

The College Years

As a computer science major at UCLA I had the opportunity to participate in a program for historically underrepresented groups—the Minority Engineering Program (MEP). If I were to credit an entity for my success in completing my bachelor’s degree, it was definitely MEP.

One of the features of the program was our problem-solving sessions led by a graduate student in STEM. The graduate student provided us with problems that were more challenging than our homework, and we were encouraged to work in groups to solve these problems. We always performed well on exams, and, to this day, I try to incorporate elements of these problem-solving sessions in my classrooms. MEP also helped us secure summer internships as freshmen, and I received an opportunity to work at IBM in northern California. That summer was important for two reasons. I was finally able to experience life in the U.S. outside of the L.A. metropolitan area. Unfortunately, the experience also reinforced the way my computer science classes made me feel—very inadequate. Many of my classmates owned computers and had been programming for years while I couldn’t afford a computer. It was discouraging to see my classmates finish projects ten times faster than me. I tried to continue as a computer science major, but I was enjoying my math classes more than my computer science classes. Instead of seeking out the mentorship I needed, I decided to switch from computer science to math.

I definitely do not recommend that anyone do this.

My first quarter as a math major started off on the wrong foot. I was taking linear algebra, and I did not form a study group nor did I seek help from my teaching assistant (TA) or professor—I decided that I could handle this class by myself. But, when my TA returned my first homework assignment, I was really contemplating switching to history. My TA wrote something akin to, “we do not write two-column proofs in upper division mathematics.” I received a zero for that assignment, and I remember being upset when I received a 61/100 on my first exam. The curve meant that my D would count as a B, but I was still wondering if I had made the right choice.

In any case, at this point in my career, I obtained a job at the Academic Advancement Program (AAP) as a tutor for an Introduction to Linear Algebra course. AAP focused on providing support for underrepresented students in the College of Letters and Science, and the culture of AAP provided the support and community I needed to succeed. In particular, tutoring the Intro to Linear Algebra class forced me to learn how to read a math book. Not only did this help me become a better tutor, but I also learned how to prepare for my math classes. I applied this technique to my own linear algebra class and I was astounded to find out that I didn’t need to take as many notes in class because I already understood about 50–70% of the material. The lecture answered all of my questions, and I ended up earning an A. In fact, I earned an A in every math class except Probability and Statistics, and at this point even though the evidence suggested that I could pursue an advanced degree in math, I was still unsure.

Career Path 1

I enjoyed tutoring—it felt good to help someone with mathematics. Since I wasn’t aware of my career options, I decided to give teaching a shot. Our math department had an arrangement with the College of Education where you could start their credential and master’s program as a senior and have your credential and master’s one year after graduation. I asked my math advisor for her opinion and confirmed that it was a good plan. She also mentioned that my GPA would ensure that I would be accepted. I sometimes wish that she had said that my GPA also made me a good candidate for a PhD in mathematics.

So I set out to ask for a letter of recommendation from my differential equations professor, and I was stunned by her response. She said that it would be a “waste” if I became a high school teacher. I was upset because she was reinforcing my parents’ feeling: they also thought that I would be wasting my talent as a high school teacher. But I truly felt that I could be an agent for change if I became a high school teacher in Baldwin Park to change lives by empowering students with mathematics. It took me a while to understand what my professor and parents meant, but I’m glad they shared their thoughts with me.

I have never forgotten what my differential equations professor said because deep down I knew that she wanted the best for me. In any case, one benefit of having earned a master’s in education was the fact that my eyes were finally open to the injustices so many of my brothers and sisters faced around America and in my hometown of Baldwin Park. Those two years spent learning about education in America helped me understand that I was “lucky” to have gotten this far. I also learned that I could do more than just teach mathematics—I could use mathematics as a driver for social justice. Mathematics could open doors that would allow my brothers and sisters to fully participate in our society.

Teaching is a Noble Profession

I loved teaching high school—I taught for a total of eight years—and I especially enjoyed the six years that I taught at my alma mater. I have enjoyed watching my students grow and become successful adults. They inspired me to be the best that I could be for them every single day so that they could pursue their dreams. They also challenged me to keep growing by asking me, “what comes after calculus” and what it meant to pursue a graduate degree in math. I didn’t know how to answer, but I was fortunate to meet someone who was going to drastically change my life because she believed in me more than I did—Melissa, my wife of almost 14 years.

Melissa and I met in 2000, and she was so excited about math that she gave me a hug when she found out I was a math teacher. She also helped me reflect—I spent a lot of time helping students fulfill their potential, yet I had not done so. Moreover, she noted that I truly had a passion for math, was pretty good at it, and owed it to others to fulfill this potential. If I truly wanted my students to have access to the opportunities that were denied to our community, then I needed to explore how to gain such access myself and share my knowledge. It took me a while to gather the courage, but at thirty, I enrolled in a master’s of arts in math program at California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB). A year later Melissa and I were married and I finished my degree in 2008. I took a small detour to earn a little extra money for our families in 2008, but by 2010, we were in Iowa where I was set to start the PhD program in mathematics.

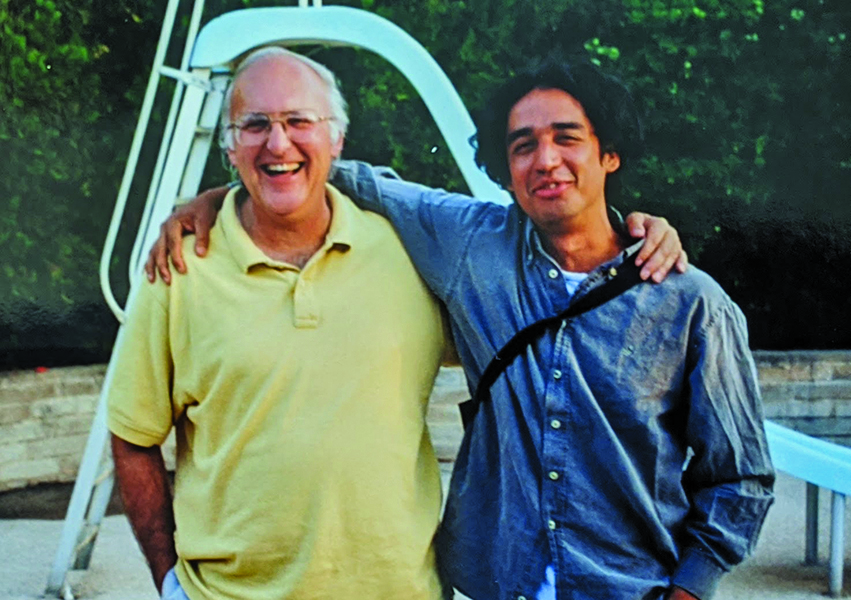

People always ask me how someone from Baldwin Park ends up in Iowa City. Frankly, I finally found the mentorship that I needed. Melissa introduced me to her advisor and LSAMP director at CSUSB, Dr. Belisario Ventura. I was searching for a PhD program that supported their students the way that MEP had supported me at UCLA. The first school he mentioned was the University of Iowa. Melissa and I arranged a road trip and in 2009 visited the University of Iowa where we met Dr. Phil Kutzko. Phil invited us to return to the Field of Dreams conference a week later and sure enough Iowa students were able to confirm Dr. Ventura’s recommendation.

At 35, I enrolled at Iowa and started fulfilling a dream that I could never imagine. Having life experience made it easier to navigate the difficulties of a PhD, but the community at Iowa was also instrumental. Melissa and I met many friends who became part of my support network as we completed the journey together. Many professors at Iowa cared about our well-being, and I was blessed that my first algebra professor at Iowa was Dr. Frauke Bleher. Frauke’s class confirmed that my favorite topic in math was abstract algebra, and I could not have asked for a better research advisor. Frauke helped me grow as a mathematician, a writer, a presenter and was instrumental in making sure I conducted research on specific finite-dimensional k-algebras.

Dr. Kutzko also helped me navigate the guilt I felt for pursuing pure mathematics as opposed to applied mathematics. My parents had instilled in us a desire to serve our community, which was easy to do as a high school teacher. As a pure mathematician, I felt that the math I was producing was not truly helping my community. But he reminded me that first of all, the act of obtaining a PhD in pure mathematics meant that I was helping to hold the door open for other minorities to walk through. Moreover, we never question the contribution that art and music have on society, and, likewise, pure mathematics has something to offer humanity. But finally, becoming a professor of mathematics would also enable me to return to my community and share what I had learned on my journey.

Career Path 2: CSUF and Beyond

I am now an assistant professor of mathematics and math education at a place that is a great fit for me—California State University, Fullerton. Most of our students are first-generation. We are both a Hispanic- and minority-serving institution. I meet many students who, like me, are navigating a university system that can sometimes feel daunting. Many of my students also love math, but are not sure what to do with their degree. They like the idea of graduate school, but are not sure how they’re going to finance it, not knowing that tuition is covered, and you also receive a stipend to earn a PhD. My current research also focuses on helping faculty develop their pedagogical skills to create classroom environments that are rigorous, inclusive, diverse, and equitable. And, although I have published a few papers in mathematics, I see that my time as a mathematician is now better spent in helping young mathematicians find their path.

In the last five years, I have advised nine undergraduate research projects with nineteen students. My students and I have also collaborated in establishing a community of minority scholars that is focused on helping everyone rise. My students make me proud every day—for starting an inclusive research club called PRIME (Pursuing Research in Mathematical Endeavors) that focuses on opening doors for others, for overcoming many obstacles in their pursuit of excellence, and for teaching me that our feelings about math are as important as what we know in mathematics.

Our family is now growing—my wife and I just had a daughter—and I want her experience to be even more privileged than the one I had. But I also want her and her cousins to live in a world that values their lives, and the culture that they bring to the table. And I also want my daughter to learn not just from my experiences, but from those that my parents have shared with us. Our success has only been possible because of them and their bravery, tenacity, and work ethic.

Advice

As I reflect upon my journey, if I could give my younger self advice, I would say “do not be afraid to ask for help.” Although I learned to be an independent learner by trying to figure out everything by myself, it also left a blind spot—there are times when you need community to help you reach higher. It took me a while to learn this lesson, but I hope my story encourages others to seek a community of people who want the best for them and challenge them to fulfill their potential.

This is exactly who I try to be for my students. I invite them to be part of our mathematics community at CSUF. My first assignment for students is that they turn in a syllabus quiz in my office so I can get to know them and start breaking down barriers. I listen to their goals and aspirations, and I mention opportunities that might be of interest to them. I invite them to our PRIME Club meetings and I encourage all to join a club. And I challenge my students to overcome the doubts that creep into all of us. Many of my students wonder if they’ve made the right decision. I try to tell them that most of their choices are not right or wrong, but have consequences that we can learn from to become better.

This is how I try to overcome the challenges that come from being a Latinx/Hispanic mathematician and educator. The biggest challenge for me has been in reconciling my identities. I went through life thinking that I had to be two different people—a person at home who is different than the one at work. Indeed, the toughest challenge has been balancing my life as a son, brother, husband, and father with my roles as a teacher, mentor, and researcher. I overcome these challenges by trying to reflect as often as possible on the choices I have to make—reflecting on if I am at peace with the consequences of my choices.

[1] La migra is slang for immigration enforcement in the United States.

Previous Testimonios:

- Dr. James A. M. Álvarez

- Dr. Federico Ardila Mantilla

- Dr. Selenne Bañuelos

- Dr. Erika Tatiana Camacho

- Dr. Anastasia Chavez

- Dr. Minerva Cordero

- Dr. Ricardo Cortez

- Dr. Jesús A. De Loera Herrera

- Dr. Jessica M. Deshler

- Dr. Carrie Diaz Eaton

- Dr. Alexander Díaz-López

- Dr. Stephan Ramon Garcia

- Dr. Ralph R. Gomez

- Dr. Victor H. Moll

- Dr. Ryan R. Mouruzzi, Jr.

- Dr. Cynthia Oropesa Anhalt

- Dr. Omayra Ortega

- Dr. José A. Perea

- Dr. Angel Ramón Pineda Fortín

- Dr. Hortensia Soto