Mexico City and the Early Years

I was born in the great Mexico City. Here the adjective great applies to many different things. First, the Mexico City Metropolitan Area is large and densely populated. People of all colors and creeds coexist within its boundaries. At the time of this writing its population is estimated at 21.7 million, and within the city limits the density is estimated at 15,600 residents per square mile.

In its second form of greatness the city has a rich history and is deeply cultural. According to a legend, the Mexica tribes traveled thousands of miles looking for the land where they were to settle. As they walked through a valley surrounded by mountains they found an island within the Lake Texcoco. There, perched on a cactus, was an eagle with a snake dangling from its beak. This was the sign. The settlement grew to become the capital of the Aztec empire, the largest city in the American continent. Tenochtitlán was founded in the fourteenth century by the Mexicas. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived it was a prosperous city with a sophisticated socio-economical system and urban architecture.

In his 1576 book Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España, [1] Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote:

“When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments […] on account of the great towers […] and buildings rising from the water […]. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? […] I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.”

The Spanish conquered the city in 1521, and built Mexico City on the ruins of the great Tenochtitlán. Throughout the centuries, the lake was drained and the city expanded over it. Every time an earthquake hits Mexico City its citizens are reminded that they live atop the ancient lake bed. From one of my favorite spots in Mexico City one can witness 500 years of history: the Templo Mayor (built between the fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries), the Metropolitan Cathedral (built between 1573 and 1813), and the Torre Latinoamericana (Latin-American tower, built in 1956). The photos above give a glimpse into the rich culture of Mexico.

The next measure of greatness is not as captivating. During my childhood the city regularly broke records levels of pollution and crime. Life amidst daily chaos was challenging. Home, family, and school were my protection, and schoolwork was the crutch I leaned on as I navigated the winding path from childhood, through puberty, and into adulthood. Outside the bubble there was turmoil. The 1980s started with one of the worst presidents in Mexican history. The ensuing years of financial instability were felt at all levels of society, with the rich getting richer, the middle class shrinking, and the poor falling in the depths of misery. We dealt with family tragedy, and lived through the earthquake of September 19, 1985. The 8.1 magnitude earthquake started at 7:19am and lasted almost four minutes. We were used to the occasional movement of the earth, but this was different. Thankfully our house was not built on the lake bed, and it was not damaged. When the earth stopped moving we tried to get over the fright and continued with our morning routine; after all it was a school day and we could not be late! It wasn’t until we got in the car that the news of widespread damage reached us through the radio. Ten minutes into our trip, we turned around and returned to our home. Schools were closed for many days. I volunteered at the Red Cross, was given gloves and asked to go through a mountain of debris, in search of lost personal belongings. At least I felt that I was doing something to help, and millions of people came together as the government struggled with their response. This experience taught me early on about the power of grassroots efforts and the need to have empathy, believe in our community and cater to it.

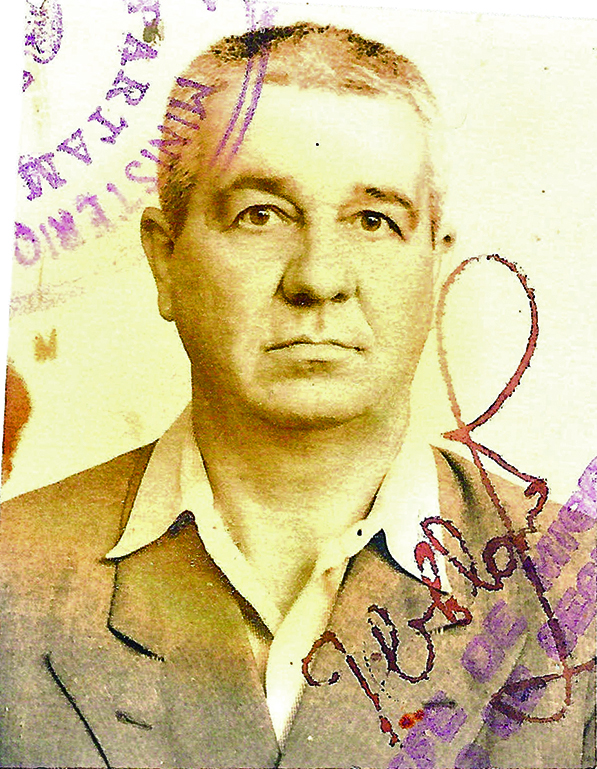

Family

In the face of adversity we always turned to family unity and to education. Education is life insurance. Instead of favoring a fancy house, or a move to a neighborhood that would cut down on our daily commute, instead of indulging in expensive vacations, my parents prioritized education. They chose to pay for tuition in a school that was to provide me with the foundation needed to succeed in my later studies. Still, in the social context of our country, we were among the privileged. I understood this and have never taken it for granted.

In the first half of the 1980s, when the crisis hit the hardest, our vacations consisted of day trips to the many small communities around the city, and bi-yearly trips to see our grandparents in Mérida and Campeche, two beautiful cities in the Yucatán peninsula. The road trip lasted between 16.5 and 22 hours, depending on traffic and on road conditions. My dad did not like to stop and often chose to do the trip in one go. I dreaded the gas station bathrooms, and got nauseous in the car. So I slept, as much as I could. Once we arrived to our destination our wonderful grandparents awaited us along with crates of mangoes and other tropical fruits, coconut water, the smell of the tropics, and the movement of sunlight on the water. It felt like paradise, and we immediately forgot the nuisance of the trip. It was worth it. I learned the value of family, and that personal sacrifice is outweighed by giving joy to others. As tweens and teenagers it would have been easy to whine our way into staying home. That would have been a tremendous loss.

Discovering Mathematics

I had a happy childhood, surrounded by a strong and loving family. I remember fondly the frequent weekend outings to the city’s parks or one of the forests in the outskirts of Mexico City. As a little child I loved counting and finding patterns. Every time I had a set of items at hand, I sorted them into similar shapes and colors, and I counted them. I also loved to see geometrical patterns around me. These ranged from daily occurrences on tiled floors and walls, to the painted or embroidered patterns on the artisan work that we saw during our trips. I admired those extraordinary geometrical shapes carved into the stone temples of the Aztec, Mayan, Olmec, Toltec, and Zapotec cultures. I also saw patterns in nature, twisted twigs, entangled seaweed, the intertwining of the waves, and the interplay of light and movement during a sunset on the water. To me, math went beyond numbers. It also consisted of shapes, colors and movement, and it was partly art. As the years passed, my love for mathematics grew. Mathematics was everywhere, but the idea of devoting my life to it, was quite abstract. I did not know that one could do math for a living, and thus I assumed that I would become an engineer, like my father and grandfather.

At school, I worked extremely hard and started building my vision for the future, however uncertain it felt. In high school, I focused on math and science. The discovery that I could become a mathematician made me very happy. In my senior year I learned about DNA and fell in love with molecular biology. As the time to apply for college approached, I perceived the private universities as too narrow and limiting in their offerings. I had a thirst of knowledge and it soon became clear that my ideal school was the national university. The math curriculum was flexible and enthralling, most courses looked fascinating. Studying math seemed to necessitate giving up biology. I convinced myself that I could become a mathematician and later pursue a master’s degree in molecular biology. Although the plan was unconventional, I persisted. I always followed my dreams.

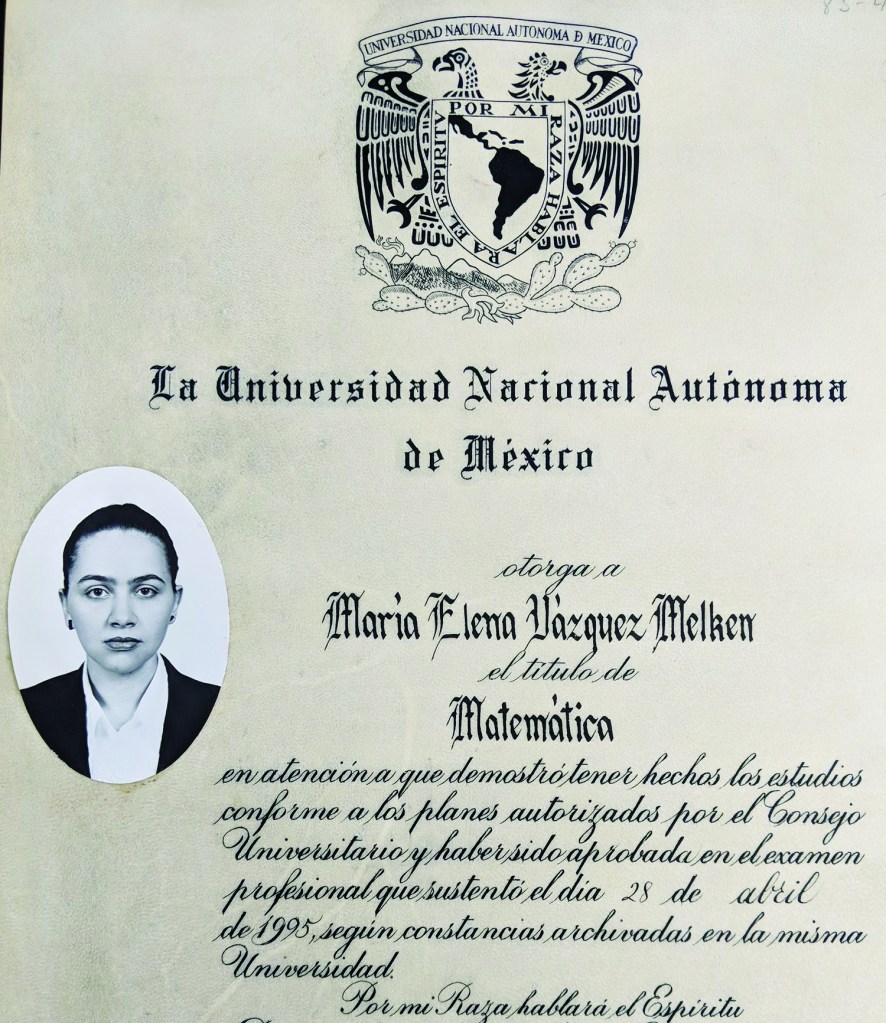

My transition from high school to college was smooth. The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) offered me a first-class education. And it was free of cost. The transition from the tight bubble that enveloped me through high school to a university system that, in 1990, enrolled more than 271,000 students, employed 28,000 academic personnel and 25,600 staff members, may have seemed daunting. I thrived. I flourished in the immensity, the beauty, and the cultural offerings on a campus fittingly called Ciudad Universitaria. [2] Each day, the sensation as I entered the campus was that of coming home.

La UNAM

In Mexico, university students live with their parents whenever possible. Those who have to move away from their hometown to attend college live with extended family, primos, tíos, abuelitos. [3] In the absence of extended family, students, especially women, lived in vetted and ‘respectable’ guesthouses. The university had no dorms, and the rental market was intimidating and not affordable. Most also perceived living alone as dangerous, and a sign that you were devoid of your family’s protection.

I stayed home, with the caveat that my home was far from the university, even by Mexico City standards. I lived in the northwest of the metropolitan area, while the university was located in the southwest. Distance is relative in Mexico. One can measure the absolute distance, which in this case was a mere 25km (approximately 15 miles). The temporal distance was more practically relevant, and it varied from 25 minutes in the wee hours of the night (2 am, for example), to 45 minutes if you were lucky and your commute was light, and up to two hours on the worst of normal days. Abnormal circumstances included road flooding after a storm or road blockage due to a crash, construction or one of the frequent marches for social justice. On those days you had better stay put and wait until late at night to attempt the commute back home. Of course, the temporal measure of distance had to be weighed by the means of transport. I was fortunate enough to own an old car that I could use for my daily trek to University City. Most citizens did not have that luck. Commuting by public transportation meant taking one or two small buses (the infamous peceros) to the nearest subway station, transferring twice, and finally arriving at the University City Station which was a ten-minute walk from the math department. All in all this was an exhausting 2.5-hour one-way commute. When driving I had to leave my home at 7:30 am to make sure that I made it to my 9 am class. As the years went by and traffic worsened, I left earlier and earlier. Leaving at 6:45 am would cut the traffic in half allowing me to cross the city in 45 minutes, arrive early and study on campus, or take the occasional 8 am class. My preferred commute was a hybrid: leave home at 7:15 am, drive for 30–40 minutes to Colonia Roma, exercise, grab a coffee and take the subway into campus.

Occasionally, I commuted with a friend. It was good to have someone to talk to while braving the road rage and the traffic in Mexico City. He once told me that if I didn’t become a mathematician I would surely find a job as a cab driver. I learned every possible route and shortcut on my way to school. My mission was to not sit in traffic, so I often ventured off the main road, and developed a useful skill. It sounds funny, of course, but underlying it was a sinister cause: pollution and road chaos get on your nerves. They generate mounting anxiety. A few times I felt on the verge of breakdown. Optimizing my trajectories from point A to point B in the city entertained my brain and kept it from going to dark places. Unbeknownst to me, this presaged my future interests in random polygons. After all, each trajectory from home to college and back was a polygon in three dimensional space, whose embedding was affected by the fourth temporal dimension (time of day, day of the week, etc.) and by the randomness conferred to it by the city itself. Observing the world around us, and navigating it, teaches us about shapes and about the dynamics and randomness of different processes. Even adverse situations offer opportunities for reflection and learning.

Around that time I found a deep love for theoretical mathematics. My favorite classes were those in topology, geometry, set theory, number theory and graph theory. I started attending the national meeting of the Mexican Mathematical Society, and the Graph Theory Colloquium, soon yielding to the prospect of becoming a researcher. I am grateful to so many wonderful teachers, to my classmates, to our philosophical musings and love for math, and to the flexibility of the system.

At UNAM there were no majors or minors. The college application involved a general and a topics entrance exam. I forget the exact sequence of events, but I do remember having to indicate my chosen subject, as well as second and third choices. The first choice was mathematics. The second, in case you are curious, was architecture. Admittance implied entry into the carrera [4] of mathematics at La Facultad. [5] The Facultad consisted of a cluster of buildings and subjects that included mathematics, physics, computer science, actuarial sciences, statistics, and biology. All courses were chosen from an extensive list of mathematics courses provided by the math department. The first two years were quite rigorous and predetermined, but after that the flexibility was exhilarating.

The memorable Calculus II classes from the power team, Luis Briceño and Julieta Verdugo, and Calculus IV from Javier Paéz, not only gave me strong foundations, but also taught me how to teach. To this day I find myself shaping my lectures inspired by theirs, with lots of in-class discussion, long homework sets, and by integrating a research project into the student assessment. Briceño and Verdugo demonstrated team science in the classroom, were fantastic lecturers, and gave students a glimpse into the work they did outside the classroom. Several times a year they offered training sessions for K–12 teachers in low-income public schools—an essential service to a population ravaged by poverty, decades of underfunding and poor teacher preparation. I remember my teachers and I am grateful for the education they delivered with passion and dedication. A fantastic teacher can change an undergraduate’s life and start shaping the mold of a future researcher and mathematician. Why then do some of our institutions, and colleagues, look down on those professors who are excellent educators, but do not do much research in mathematics? I personally think that there is room for everyone and that higher-education benefits from a diversity of approaches to teaching. Each instructor meets their students at a different level. Some will capture the student’s imagination in high school or in freshman year. For example, I learned introductory astronomy from Julieta Fierro, who on the first day of the semester, entered the classroom in roller blades, and climbed on the table to illustrate heaven in the Babylonian cosmogony. Dr. Fierro inspired a lifelong fascination for the skies and a deep appreciation for science communication. In mathematics some instructors can inspire the jump into deeper and more abstract mathematics through the calculus or linear algebra series, when a student could as easily switch to a different, not so challenging, discipline or major. Other professors can shape students dreams early on by modeling the path into abstraction and the tenacity needed to go to graduate school in mathematics and to undertake mathematical research.

Did I mention that UNAM was an oasis amid the surrounding chaos? The comings and goings of mathematicians and other scientists modeled a more civilized society where citizens look out for each other, and work hard for the sake of knowledge, with no financial interest, with the goal of educating the next generation. Our facilities were not fancy, but we had all that we needed. Education was free and all services, including books, photocopies and food were heavily subsidized. I am not familiar with UNAM’s budget model of the 1990s, but from the point of view of the student I can tell you that we had what we needed: good professors, high-quality curriculum, large classrooms (clean and with chalk on the boards), green areas, a small library and a cafeteria. Minutes away was a cluster of world-class science institutes (astronomy, geophysics, materials science, mathematics, applied mathematics) with access to top-notch researchers, and the first and largest super computer in North America. A short drive, or shuttle ride, away was the massive central library, and the school of medicine. Going southwest were the volcanic formations and the university cultural center where I saw more symphony concerts and watched more art movies than I can count; excellent offerings at a very low cost for students. UNAM catapulted me into the possibilities of my future and I am ever so grateful for that.

Knots and DNA: The Launch of My Career

After taking the core courses I started leaning towards the theoretical math offerings. I took two number theory classes from the legendary Alberto Barajas, one of the founders of modern mathematics in Mexico. I learned graph theory from Neumann Lara, a wide range of the topology and geometry offerings from Bracho, Clapp, Montejano, Eudave, Gómez Larrañaga, González Acuña, Neumann Coto, four semesters of analysis from Grabinsky and Carrillo, set theory from Amor. Back then I thought of “pure” math in opposition to “applied math” and inferred that I would need to relegate my interest in molecular biology to a mere hobby. I was mistaken. One day, walking through the halls of the department, I found a poster announcing a series of lectures on “knots and DNA” by De Witt Sumners, professor of mathematics at Florida State University. This combined the math that I liked with molecular biology. I have thought about knots and DNA since that day. It has been the leitmotif of my career. This day led me to the path less traveled and shaped my future. Work as hard as you can and follow your dreams as they will take you exactly where you need to go, even when the path may seem unconventional.

An undergraduate thesis is a graduation requirement for college students at UNAM (and most other universities in Mexico). I have often claimed that a third of what I learned in college I learned while writing this thesis. In bulk amount of material the thesis can probably not even come close to the hundreds of derivatives, limits, and integrals solved in the calculus series, but if we consider the content weighted by its future impact, the thesis largely overtakes the rest. That being said, doing research would not have been possible without the foundation acquired during the first few semesters of my college years. Beyond enjoying the details of the work itself, writing a thesis moved me into the world of mathematical research. I became an undergraduate scholar in the math institute, attended national and international conferences, listened to famous researchers and witnessed the lifestyle of professional mathematicians.

It soon became clear that I wanted to go to graduate school and pursue a PhD program. However, I had not asked my parents to pay for a college degree, and was surely not going to ask them to come up with tens of thousands of dollars to pay for graduate school. The idea of applying to a PhD program abroad did not materialize until I understood that I would not only not be expected to pay for the degree and support myself, but that the university that admitted me would pay me a student salary sufficient to support my living expenses, and would cover my tuition. I always wonder how many people don’t even start dreaming because of the fear of the financial cost. Those individuals could have brilliant careers and instead leave the pipeline.

The community supported me, and encouraged me. I received a scholarship and was admitted into a handful of prestigious universities. The choice was now easy. A few months later I boarded a plane with two suitcases and U.S. $500 in my pocket. My savings vanished in the first week of paying for necessities and various utility and housing deposits. But I was there, I was not afraid and was determined to succeed. I also had a fantastic advisor, De Witt Sumners, whose family helped me tremendously during the first few weeks.

On Being a Woman in Mathematics

I am an optimist by nature, and tend to be very positive. I feel compelled, however, to unveil some of my experiences with injustice and misogyny. These are of course not limited to my city, or to the developing world for that matter, but I did not know it when I was young. We always think that the grass is greener on the other side. When I lived in Mexico it was impossible for a woman to walk in the street without being catcalled. For teenagers or young adults, the verbal attacks were vicious and continuous. On occasion they transcended the verbal and the perpetrator followed you for a few blocks on foot or for miles by car, adding to your fear, the constant terror of sexual violence. At secondary school I felt safe. In college I learned to be vigilant as I traversed the city from day to day. While on campus I felt mostly safe. I learned to avoid sensitive areas and to speed up my walking from the subway to the department. Inside the Facultad de Ciencias, [6] life was good. Well, it was good until I started working as an undergraduate research assistant, attracting the attention of one too many middle-aged professors. I was very shy and kept to myself, but I was driven and a very good student. This, compounded by the oddity of a woman in mathematics, appealed to certain types. Of my freshman class of eighty, ten graduated in mathematics, with only two women. I was curious, focused and passionate about learning and breaking barriers. They also found these traits appealing. I was friendly and always carried a gentle smile. This opened the door to abuse of power. The few women doing research, most of them young students, learned to assimilate in the male-dominated world and to live with constant microaggressions in the form of false praise that some took as compliments, some relished, and most others dreaded. And then there was the joking… Many sexual or misogynistic jokes were (and still are) socially accepted. Making fun at the expense of women, minorities, and those with different sexual orientations was normalized. Oh, but do not take me wrong, this was not unique to Mexican society and the Mexican academic environment. I continued my career in the United States and the jokes continue until this day. They are less loud and are concealed under a veil of hypocrisy. There was for example the warning from a fellow graduate student to be aware that professor X just stared at your breasts while he pretended to listen to you. The misogyny in Mexico was overt and accepted, while in the United States it is closeted, but omnipresent.

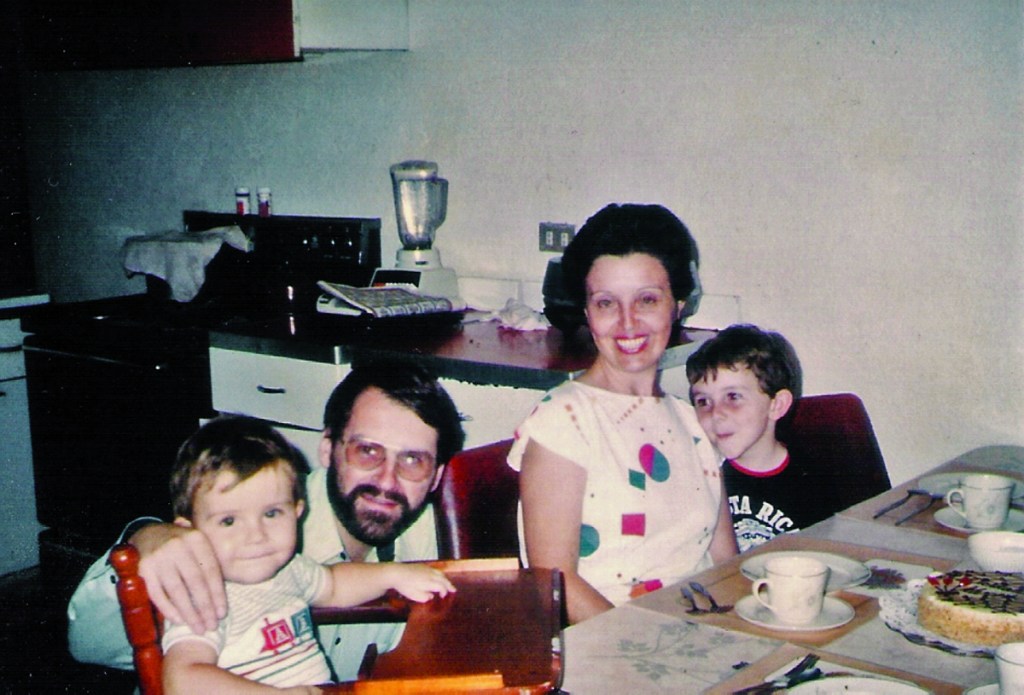

It wasn’t until several years into my move to the United States that I learned to recognize discrimination. I have to say that such naïveté and ignorance was helpful. Looking back I now remember those instances and recognize them. For example, a staff member who, throughout the PhD, confused me with the only other Latina in the program. Our names are vastly different and each of us has a distinctive physiognomy, including different skin color. Or that famous mathematician who, after seeing my husband pushing our first child in the stroller, told him that his life as a mathematician was over. We were both postdocs dealing with the uncertainty of the future and navigating our first year as parents while teaching and conducting research.

These were signs of systemic gender and race discrimination, but I always chose not to linger on them. I thought that the perpetrators were individuals (as opposed to groups) making bad choices, and I tended to give people the benefit of the doubt. I still do, and I am the better for it. My approach has been to distance myself from them. Ever the empath, I rationalize what could have caused the behavior. I do not (or try not to) take it personally, brush it aside and keep moving forward. We make choices in life and the choice to allow the attacks of others to hurt us is one that shapes who we are. There is adversity in life. We cannot know when and where it will strike, but we can choose how much we will allow it to weigh us down. This, I recognize, is easier for those of us who grew up abroad, nevertheless, we have a responsibility to recognize injustices, step up to protect others, and continue moving forward, one step at a time.

Conclusion

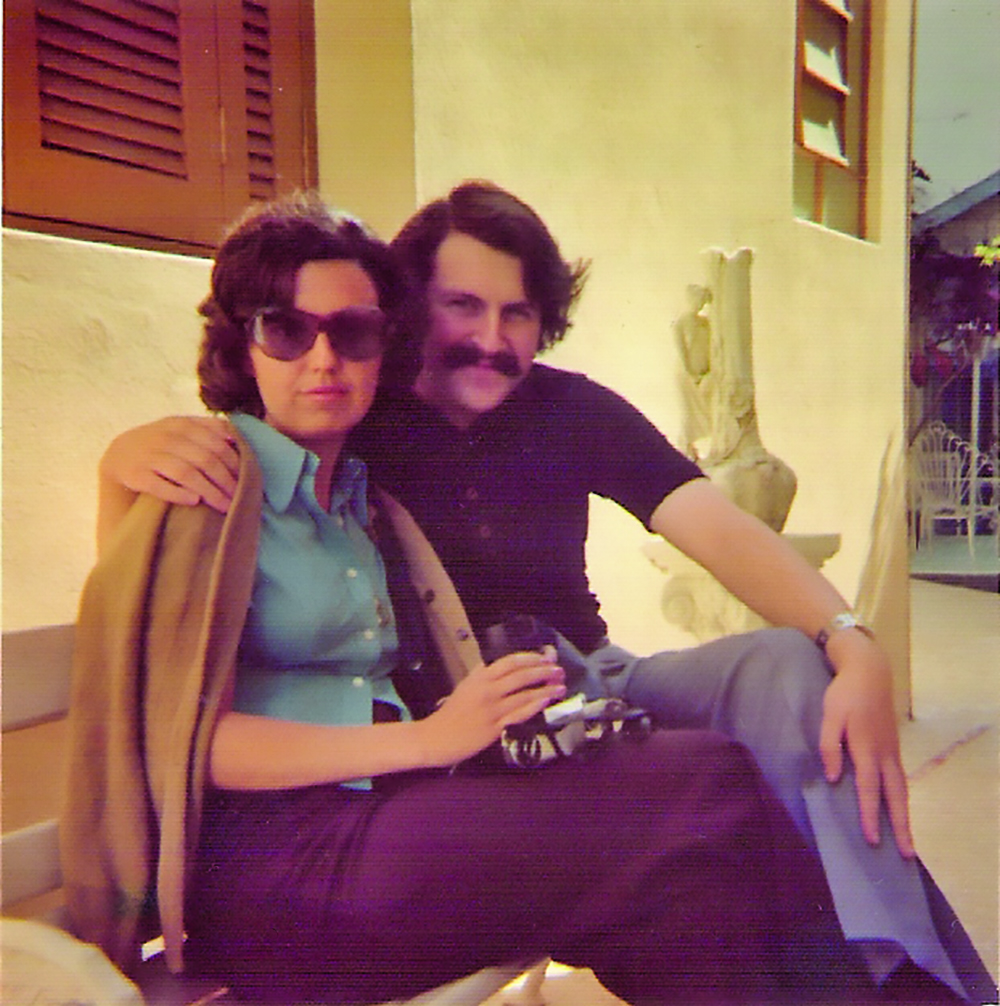

Today, fast-forward two decades, I am a full professor in the departments of mathematics and of microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of California Davis. I am married to my collaborator, life partner and best friend, Javier Arsuaga, and we have two beautiful children. I devote my research life to studying the molecular intricacies of genomes and the inner working of proteins that interact and change the topology and geometry of DNA. I co-lead a research group with my research and life partner. I find much joy in mentoring students in research and in communicating science at all levels. The other half of my academic life is devoted to combating inequities and providing an equal playing ground for all. I lead the Center for Multicultural Perspectives on Science (CAMPOS) whose mission is to support the discovery of knowledge by promoting women and other groups underrepresented in STEM, through building an inclusive environment. My academic and personal lives intertwine like the DNA double-helix. For now, while still young, our children follow their parents in the uncertain winding path through life. There have been many hurdles, but it is always about looking up and moving forward, with patience and concentration, putting one foot in front of the other. This is a story for another day.

[1] The True History of the Conquest of New Spain

[2] University City

[3] cousins, uncles/aunts, grandparents

[4] career

[5] the Faculty of Sciences

[6] College of Science

Previous Testimonios:

- Dr. James A. M. Álvarez

- Dr. Federico Ardila Mantilla

- Dr. Selenne Bañuelos

- Dr. Erika Tatiana Camacho

- Dr. Anastasia Chavez

- Dr. Minerva Cordero

- Dr. Ricardo Cortez

- Dr. Jesús A. De Loera Herrera

- Dr. Jessica M. Deshler

- Dr. Carrie Diaz Eaton

- Dr. Alexander Díaz-López

- Dr. Stephan Ramon Garcia

- Dr. Ralph R. Gomez

- Dr. Victor H. Moll

- Dr. Ryan R. Mouruzzi, Jr.

- Dr. Cynthia Oropesa Anhalt

- Dr. Omayra Ortega

- Dr. José A. Perea

- Dr. Angel Ramón Pineda Fortín

- Dr. Hortensia Soto

- Dr. Roberto Soto

- Dr. Richard A. Tapia

- Dr. Tatiana Toro

- Dr. Anthony Várilly-Alvarado