Why Math

I have always been drawn to beauty and order, two concepts central to mathematics. I grew up in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York—a wonderful land on the south shore of Long Island (right near the beach). The ocean has always been a tranquil escape for me, and I’ve always felt a connection to my ancestry through the shared experience of the ocean. As a child in the early 1980s, I reluctantly spent many hours (on both weekends and weekdays) with my parents at church. Rather than engage with the spoken gospel, I would admire the interior of our church, St. Mary’s Star of the Sea, and take in the physical gospel that was presented before me. During these long masses, I would get lost in the lights and the architecture. I loved the symmetry and the grandeur of the altar and how that stately mirror-like design was continued throughout the entire building. I was especially hypnotized by the stained glass of the stations of the cross and the stylized geometry of the figures contained in each of the colorful panes of glass. Each image made more beautiful by the mid-morning sunlight. One of my earliest memories is waiting outside of the church after my brother’s youth bible study group, Las Jornadistas, got out. All of the young people were happily chatting and milling about before walking home. My brother and I got a rude surprise when we realized that his bicycle—our only mode of transportation at the time—had been stolen while we were in church. To this day we still marvel that someone would steal a bicycle with a baby seat attached from a church! It takes all kinds.

My homeland, New York City, is a melting pot of people and cultures, and Rockaway, Queens had a similar mixture of cultures, but on a smaller scale. Rockaway Beach is a long peninsula on the south side of Long Island with a long swath of sandy coast facing the Atlantic Ocean. Rockaway Beach is defined by Breezy Point on the western border and Far Rockaway (where I was born) on the eastern border. All types of people are drawn to this area because of the beach and relative proximity to New York City, but the neighborhoods are somewhat segregated. Breezy Point tended to be more well-to-do and working class people of European descent. Many of my friends from this area were Irish Catholics. Breezy Point, Neponsit, Belle Harbor, Rockaway Park and Rockaway Beach are home to many of the firefighters of Irish descent who responded to and unfortunately perished in the 9-11 attacks on the Twin Towers (may they rest in peace). As you move further east on the Rockaway Peninsula into Arverne, Edgemere, Bayswater, and Far Rockaway, you would find the homes of the Black and Latinx Rockaway residents. The easternmost border of Far Rockaway was (and is) defined by a large orthodox Jewish community, beyond which lay the suburbs of Nassau County, what many people call the start of “Long Island” (though all of Brooklyn, Queens, Nassau and Suffolk define Long Island).

My Familia

If your family is anything like my family, every family function is the same. It didn’t matter if it was a baby shower, kid’s birthday party, quinceañera, wedding, graduation party, or a funeral:

(1) There would be food.

(2) There would be drinks.

(3) There would be music.

(4) There would be dancing.

There would be your entire multi-generational overflowing family. The adults would dance and drink while the kids would go off with their snacks (popsicles, empanadas, and/or birthday cake) to play Hide-n-Seek, tag, or Nintendo (I am classically trained on the original NES, if you’re wondering). My family is almost exclusively Panamanian, it’s mainly my generation that has started “mixing” and marrying non-Panamanians (ay Dios mio!). Panama is a beautiful tropical isthmus with the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans on either side. We love our sancocho (soup), frituras, tamales, arroz con pollo, arroz con habichuelas, and most dear to our hearts, PLATANOS (plantains). Both of my parents emigrated from Panama when they were young—my mother when she was 14, and my dad when he was 18—both looking for a better life. They found each other after moving to New York City at—you guessed it—a Panamanian party. They married shortly after meeting, moved to Brooklyn, and started a family immediately. My two brothers Oscar and Omar were born within one year of each other, more than a decade before me.

My father assures me that the family was not quite complete until I appeared, he says “siempre queria una hembra,” [1] and 12 years later, I made my appearance on this earthly plane. My mother assures me that all of her children were accidents, something I don’t doubt considering the lack of sex education in Panama City and New York in the 1950s. By the time I was born our family had moved into a house in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York, where we often held family gatherings in our basement, in our backyard, or at the beach.

Everyone in our large extended family hosted family gatherings. My grandmother, Nana, was the matriarch of the family and frequently hosted us all in her home in Cambria Heights (Queens). My grandmother meant the world to me and I probably spent half of my childhood in her home.

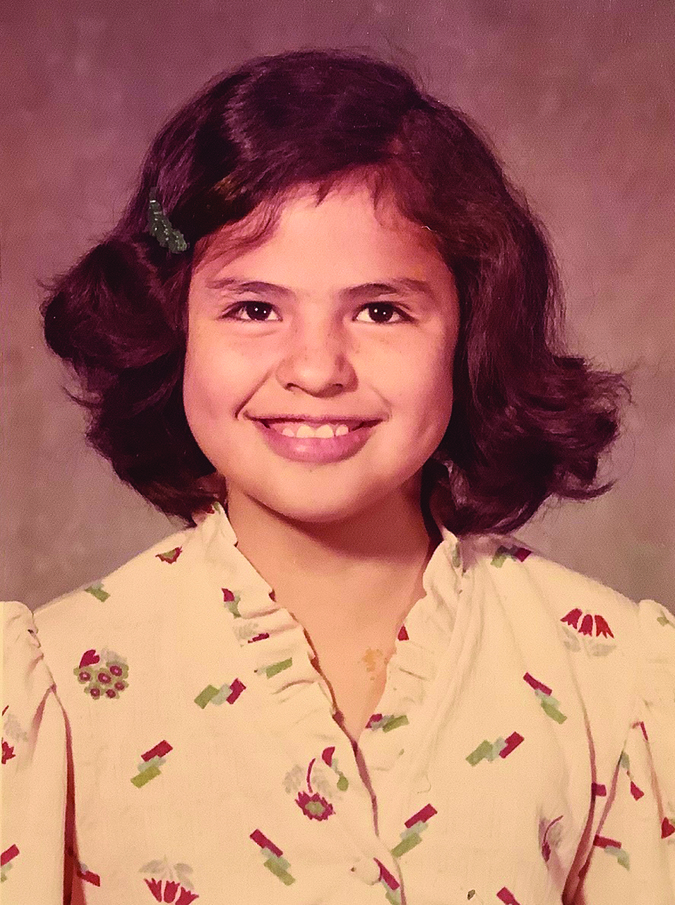

Early Education Years

I remember after starting elementary school she asked me why I let my friends in school call me Oh-My-Rah, and I remember her face twisting up to say the letter ‘R’ in her most exaggerated American accent. I didn’t know how to ask people to say my name correctly. I didn’t know how to take up space yet, and I’m not sure that I’ve fully learned that skill even now, even though it means the world to me when people try to say my name properly. The very first time a teacher said my name correctly I was in college. I honestly almost cried when my ethnomusicology professor, Katherine Hagedorn, said my name correctly without any instructions from me. It has happened again, but it is still rare. It’s especially hurtful when people don’t even try to get my name right and insist on butchering it like it’s not my own name, and they somehow know how to pronounce it better than I do. FYI—single ‘R’s in Spanish sound just like a soft American ‘R,’ so you should not roll them (like a double ‘R’ in Spanish), and your American mouths should not have a difficult time executing them—it’s in your tongue’s lexicon! You can do it! (Si se puede!)

Another important host for our family gatherings was my Tia Marta. This tia [2] made some of the most delicious food in our family. She was always ready with a FEAST. I should add that this tia was not a blood relative, but had been partially raised by my grandmother. I have a very large family, in part, because if a family friend spent enough time with us and had integrated themselves into several generations of our family, then they became family themselves. I think it is age that designates whether the person becomes an aunt/uncle or a cousin, but once they are part of the family, so are all of their descendants. Eventually they become blood. We also never differentiate between first cousins, second cousins… you’re just a cousin, and that is that. My tia had a daughter who was a constant in my early life. Our mothers were pregnant around the same time and my cousin was born 11 days ahead of me. We lived in the same town, and were the only girl-children in our generation, so we went to the same pre-school, we had frequent play dates, we would sit together at church, we even had a joint first communion celebration.

She was my very first friend and my BEST friend. When we started kindergarten at P.S. 183 in Rockaway Beach, Queens, I assumed that she would continue to be in my class since we’d been inseparable since day one (literally). I knew that I was going to be enrolled in the Astor Program for Gifted Children because of some tests I had taken, but my five-year old mind didn’t really understand the implications of this. I was heartbroken when we were separated and she wasn’t in my class.

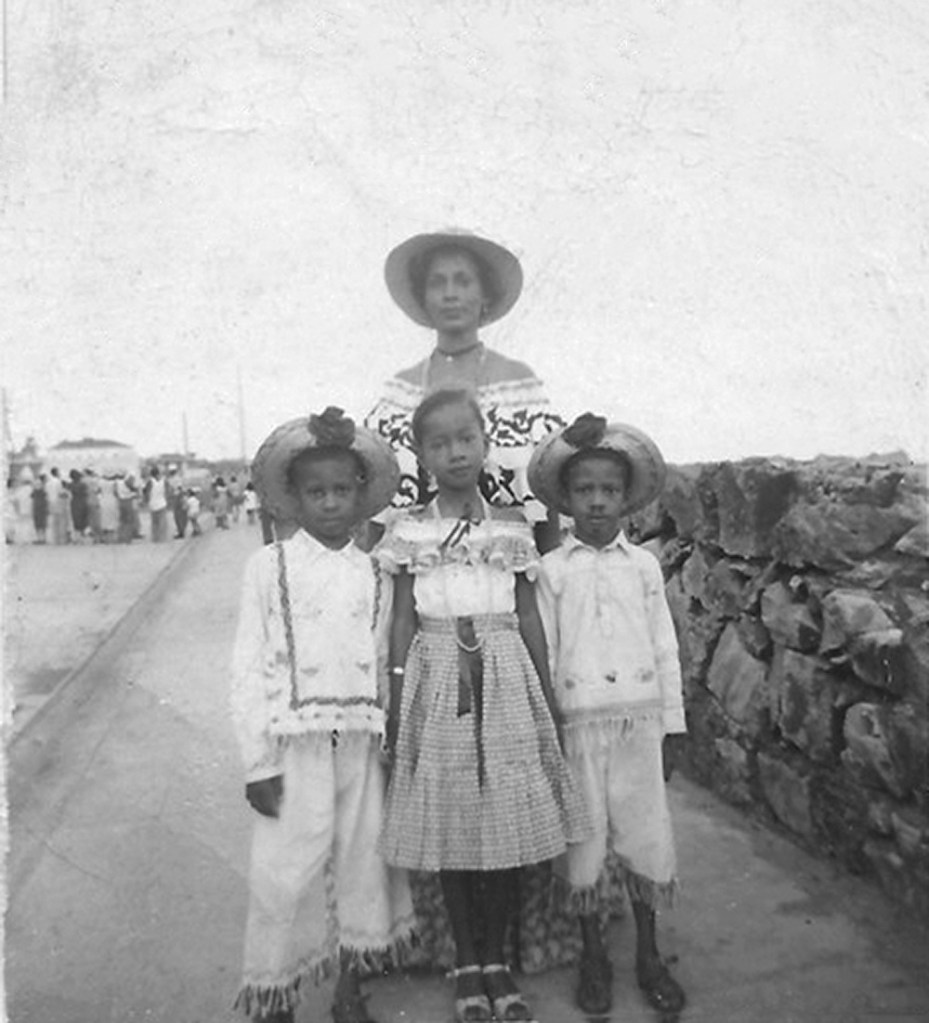

Dr. Ortega’s grandmother’s and children’s immigration to the U.S.

At the time, the New York Public School System was tracked. Upon entering, students were sorted into one of three tracks: either the Astor gifted track, Regular Education, or Special Education. I felt honored to be in a class with other “gifted” children—I loved the new things that we were learning—but even then, it felt wrong to be separated from my cousin who, up until that point, I had spent my entire life with. I missed the comfort of her company and I didn’t know any of the other pupils in my class.

There was one Astor class for each grade and the racial breakdown of the students between the three tracks was stark, even to a five-year old. Most of the students at P.S. 183 were Black or Latinx. These two subgroups defined almost 100% of the Special Education and Regular Education classes at that school. However, out of the 35 pupils in my kindergarten Astor class, only seven of us were Black or Latinx; the remainder were white. The contrast was so stark to my young eyes, and I still remember the full names of the other six. These numbers grew slightly each year, but never enough to tip the balance. The segregation that I observed on the Rockaway Peninsula seemed to have been maintained in my elementary school classrooms and would be a theme throughout my life.

When I was around 12 years old I was nominated to apply to Prep for Prep 9 by my teachers at J.H.S. 180. Prep for Prep 9 was a program based in New York City that found talented youth from around the city and prepared them to attend prestigious boarding schools. This program changed the trajectory of my life. At a young age I decided to leave my parents’ home in Far Rockaway and move to a suburb of Boston for schooling. We all saw this as an opportunity that I could not pass up, and I was ready to leave my parents’ conservative home. While I loved spending time with my friends and family at church, the idea of “a woman’s place” was one that I could not fall in line with, so I was ready to start a new chapter in my life.

Attending Milton Academy in the early 1990s was an academic blessing and a welcome escape from my conservative home in New York. I knew that this was a great opportunity for me, but it also took me away from my family and my culture. Prep for Prep 9 had prepared me for the academic rigors, but I was not ready for the extreme wealth of my classmates and the new social expectations. I thoroughly enjoyed my four years of high school—I made great friends, did well in my classes, and held several leadership roles—but issues of race and class were always in the back of mind.

Undergraduate Education and Introduction to Mathematics

I came to the field of mathematical epidemiology in a round-about way. When my dreams of becoming a medical doctor were dashed by my lack of success in my first-year general chemistry course, I focused my attention on my double major in mathematics and music. I loved my time at Pomona College. In retrospect, I can say that moving from the east coast to the west coast was one of the best decisions that I made in my young life. I can say this now because I still live in the beautiful state of California, but, during that first year, I wasn’t so sure. The social aspects of college life were most enticing to me, and, after my first semester, I was put on academic probation. Despite “trying to do better,” I was suspended for one year after my second semester at Pomona College and had to attend another school for one year and earn a B or better in all of my classes there. I wasn’t ready to go back to the east coast (read: go back to church), so I went to live with my Tia Nory and Tio Calin in Milpitas, San Jose, California and attended DeAnza Junior College in Cupertino. It was nice living with my maternal uncle’s family. I was able to live with two cousins close to my age and experience a portion of my “coming of age” years with my family. It was a challenging year where I worked full time and took more than a full load of classes at DeAnza, but this year gave me time to reflect on exactly what I wanted out of life and out of college. Gap years were not a thing when I went to school and certainly not a thing for people like me with working-class immigrant parents, but I understand how taking a gap year can give you extra time for reflection and for establishing life goals. While I enjoyed DeAnza to the fullest by joining every musical ensemble and taking most of the music courses offered on top of taking the required transfer courses for my majors at Pomona, I knew that I didn’t want to stay there any longer than I needed to. I knew that I wanted to return to Pomona College to complete my degree and I wanted to thrive there.

After that year, I was able to return to Pomona College and continue my degrees in pure mathematics and music performance. It wasn’t all roses, but I was successful and definitely improved over my performance during my first year. During my junior year I was encouraged to apply for a summer research experience (REU). These REUs were new at the time, but are pretty common now. I spent the summer between my junior year and my senior year attending the prestigious Mathematical and Theoretical Biology Institute (MTBI) which, at that time, was held at Cornell University. This program was formative for me in that I conducted research for the very first time, met many of the people who are my collaborators and colleagues, and chose my field of study: mathematical epidemiology. I also learned what it is to work, very hard, on a collaborative project. I was able to revive my deferred dream of working in a medical field. I learned that through mathematics, I could still be a healer by working in mathematical epidemiology and public health. In this program, I worked the hardest that I ever had. We packed SO MUCH into the short eight weeks that we had together. I acquired the basic skills in math modeling and differential equations that I continue to use to this day. Those sleepless nights also trained me for when deadlines approach faster than you expect.

One of the most important memories I have from this program was when Dr. Colette Patt came and gave a presentation on the state of mathematics PhDs. I remember hearing that less than 2% of the PhDs awarded in mathematics in the previous year were awarded to people of color and less than 1% went to women of color. Those statistics made me very angry but also motivated me to pursue a PhD in applied mathematics. Those statistics haven’t changed much, so they continue to motivate the work that I do, to this day.

The year before I started my PhD program, I participated in a summer program at Spelman College that set me up for success during my first year in grad school. I am very thankful to have participated in the Enriching Diversity in Graduate Education (EDGE) Program for Women. Through that program I got a more realistic perspective of the academic and social challenges that I would face during my first year, and EDGE gave me a network of supportive sisters and allies that would help me to succeed in the early years and throughout my career.

Graduate School

I didn’t get into grad school the first time I applied, but I did get in the second time (gracias a Dios). On the recommendation of my mentor, Carlos Castillo-Chavez, I went to the University of Iowa to study mathematical modeling of infectious diseases under Herbert Hethcote, one of the founders of the field. I had never been to the Midwest, so I experienced yet another period of culture shock and then acclimation. If you’ve never experienced a midwest winter, you are a blessed individual. The University of Iowa had recently been awarded a big Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) grant from the National Science Foundation so I was very lucky to receive a fellowship to support my doctoral studies. This GAANN grant built off of the previous efforts of professors at Iowa to bring more students of color to the lush, verdant corn and soy fields of Iowa. Thanks to the efforts of professors like Gene Madison, Phil Kutzko, Yi Li, Juan Gatica, Richard Baker, and David Mandersheid, the University of Iowa Department of Mathematics won the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring in 2004. The math department at Iowa was a really warm and supportive community. Everyone helped each other if we were having trouble in classes, if we needed a ride to one of the (distant) airports, or if we needed help moving into a new apartment. I remember being so worried about my partial differential equation (PDE) comprehensive exam. I knew that I was doing fine in the class itself, but I wasn’t sure that I could complete those same types of problems in a classroom space not of my choosing and in a specified time frame. I normally worked on homework problems at all times in all spaces. I could be in my office on campus, working at a nearby coffee shop, or at home asleep, and the solution would come to me. The classroom really wasn’t where I did my best work. Several older graduate students made a point to share their study binders from previous PDE comprehensive exams and helped me to study. I am so thankful for their generosity because they helped me, not only to prepare for my exams, but allowed me to feel relaxed enough to perform at my best on the day of the exam (BTW—I passed with flying colors!).

We were also there to celebrate each other if someone in the math department had a child, passed a comprehensive exam, or successfully defended their thesis. I remember coming together frequently at Phil Kutzko’s home, always over food and drinks. I loved the constant celebrations and get-togethers within the math department, as they reminded me of the way we would celebrate family at home in New York. Most of the math department were regulars at one bar and grill on Tuesday evenings where we took over many tables with our textbooks, pint glasses, and wing baskets on ‘Tuesday Wings Night,’ and we ended the week at another bar where we would lick our wounds and recap the week during ‘Friday After Class’. I really don’t think that I could have completed a PhD anywhere else. I have lots of colleagues in mathematics now, many who did not go to Iowa (no me digas?!) and, when I hear stories about their grad school experiences, I realize how lucky I was. Nowhere else would have supported me in the way that Iowa did. I felt nurtured both academically and socially inside the department, at the coffee shops, and even at the bars.

I spent the last two years of my PhD in an all-but-dissertation instructor position at Arizona State University. Those last two years teaching full time while trying to complete my PhD were arduous. I would not wish that experience on anyone, and I highly discourage anyone from attempting to start a new position before completing their PhD. Even though it started off rough, I am thankful to have had this opportunity because it led to a nine-year career at ASU. There were many moments when I thought I should just quit and be happy with a master’s degree in mathematics and another in public health, but I am glad that I persevered. My parents felt that I might as well finish since I had come so far, but they would support me if I decided to quit. Truthfully, they had no idea why I was still in college anyway, they hadn’t quite grasped the idea of graduate school (there’s more college after college?). I truly appreciated the professors from Iowa and Carlos Castillo-Chavez, who was at ASU at that time, who would occasionally check up on my progress at conferences, through email, and text messages. Without these ever constant, “How’s the thesis going?” questions, I might have given up. I felt the weight of what I owed to these mentors and the breadth of what they knew I could achieve. I am thankful that these mentors did not give up on me when it seemed like I was dragging my feet through the last phase of my thesis work.

Because each successive step of my schooling moved me further and further away from my family, it took a lot of effort to maintain ties with my family and my culture. In some stages of my life, I was not successful or even motivated to maintain these ties. I am glad that I am able to reflect on this phenomenon now that I am an adult. In my day-to-day life, I find myself thinking more and more about how I can “decolonize my mind” for myself, for my students, and for my family. With each step in my education, I lost my connection to the Spanish language. We spoke Spanish in the household when I was little, but as soon as I started kindergarten, my parents only spoke to me in English. Even to this day, I have to work to get my parents to speak to me in Spanish. Even if I start the conversation in Spanish they naturally revert to English, to which I reply either “que?!” or “como?!” to get them to go back to their first language. Through my two brothers, I have four nieces and nephews and none of them even have a basic knowledge of Spanish. I see that part of our heritage getting watered down with each successive generation, and it makes me sad. Though I recognize both English and Spanish as “the colonizer’s language,” I’m trying very hard to keep my Spanish language proficiency up.

Applied Mathematics and Public Health

I grew up on Rockaway Beach and spent almost every summer day at the beach. I could play all day in the dancing ebb and flow of the waves. It’s one thing to see the dynamics of an ocean wave from the shore, but it can be a transcendent experience to be carried by describe the dynamics of the ocean’s waves. The poetry of mathematics is all around us, even when we are not aware. Though my love for differential equations stems from the modeling of infectious disease, I still marvel at how differential equations are applicable to so many different natural phenomena.

Mathematical modeling allows me to describe the world with mathematics. I like to think that math is a universal language and, through modeling, we can share poetry about the world that we live in. The research that I’ve conducted in mathematical epidemiology first started that summer at MTBI. I worked with two other students modeling the evolution of drug-resistance in the yeast candida Albicans, using a coupled logistic equation model to describe competition between two strains of c. Albicans in a human host and the effect of using an antifungal agent to try to control their growth. From then I always focused my work on emerging infectious diseases, new vaccines, or tropical diseases.

My research in mathematical epidemiology is grounded in the public health problems of today. Using mathematical modeling and the theoretical core of mathematics as tools, I am able to better understand and describe emergent health problems such as HIV, HPV, rotavirus, malaria, polio, and TB. My contributions to science and society improve the health community’s understanding of infectious diseases and inform policy makers on how these diseases can best be controlled at the population level. In order to be well prepared to contribute to this field of mathematical epidemiology, I simultaneously study applied mathematics, statistics, epidemiology, and public health.

Currently, I work with a fantastic set of collaborators on mathematical models for coronavirus where we evaluate different isolation strategies and their cost-effectiveness. We also developed geo-spatial models for the spread of malaria which takes into account immigration, seasonal migration (i.e., seasonal workers), and tourism between Botswana and its neighboring countries. I first met these collaborators, who are a diverse group of women, at a workshop organized by the Association for Women in Mathematics at the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics, under the name, “Women in Math Biology” (WiMB). I am incredibly thankful that I could participate in this workshop because it helped restart my research program, which had been focused on undergraduate research only for about five years. I love developing research skills in undergraduates and I still maintain my Mathematical Epidemiology Research Group, comprised of all undergraduates; I also work with the Rocky Mountain Sustainability and Science Network every summer, but it is nice to focus on my own work and publications sometimes. I am also working on a project with colleagues from Sonoma State University (SSU) and other experts from other institutions trying to identify both institutional and implicit sources of bias in STEM, starting with the math department at SSU as the pilot study. This work lies at intersection of my service work and my research, so this is an exciting new venture for me—one, which I believe, could have only happened at my current institution. My experience at Sonoma State University, though still new, has been both refreshing and eye-opening after teaching at three other institutions of higher education.

The Search for Balance and Advice

It has been very nice to finally understand that I need a balance of teaching, research, and scholarship to be happy. If I focus on just one aspect alone, I feel that something is missing. Being at Sonoma State University has allowed me to continue my devotion to my students through teaching and research, to continue my scholarship and publications in the modeling of infectious disease, and to continue my service, not only within my own university and department, but also nationally through my service work with the National Association of Mathematicians, the Association for Women in Mathematics, the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science, and the Mathematical Association of America. If there is one piece of advice that I can give to folks about to embark on a career in mathematics—one piece of advice I wish that someone had given me—is that you should thoughtfully choose the institutions where you will work, study, and devote large swaths of time, based on your interests and the type of life balance that you would like to have. Don’t be afraid of changing institutions if the institution that you start your career at is not a good fit for you. It’s better to have a delayed start than to finish at an institution that doesn’t work for you or, worse, not finish because you were at an institution that didn’t work for you. I didn’t always make the best choices initially, but that is really how life experience works. I am, and always have been, on the right path—my own path. Hold tight to your culture and your life goals. Use them as your North Star and Southern Cross to navigate the inevitable ebbs and floods that will cross your path.

[1] Translating to “I always wanted a little girl.”

[2] Aunt.

Previous Testimonios:

- Dr. James A. M. Álvarez

- Dr. Federico Ardila Mantilla

- Dr. Selenne Bañuelos

- Dr. Erika Tatiana Camacho

- Dr. Anastasia Chavez

- Dr. Minerva Cordero

- Dr. Ricardo Cortez

- Dr. Jesús A. De Loera Herrera

- Dr. Jessica M. Deshler

- Dr. Carrie Diaz Eaton

- Dr. Alexander Díaz-López

- Dr. Stephan Ramon Garcia

- Dr. Ralph R. Gomez

- Dr. Victor H. Moll

- Dr. Ryan R. Mouruzzi, Jr.

- Dr. Cynthia Oropesa Anhalt